by Alfred Tennyson

Ed Friedlander MD

scalpel_blade@yahoo.com

No texting or chat messages, please. Ordinary e-mails are welcome.

And we colonized outer space because of our poets?

And what the poets told us wasn't true?

In 1829, nineteen-year-old Alfred Tennyson (he went by "Fred") won the Chancellor's Medal for poetry at Cambridge. The assignment was to write a poem on the subjet of "Timbuctoo."

The subject was not really surprising. This was the beginning of European colonization of the interior of Africa. There were legends of a great civilization in what is now Mali. Timbuctoo had been visited by a modern European for the first time in 1826, by the Scottish explorer, A.G. Laing, who was murdered soon after.

Tennyson's father urged him to enter, writing "You're doing nothing at the university; you might at least get the English poem prize."

Tennyson reworked a poem which he had written at age 15 ("Armageddon") to meet the subject requirement. "Armageddon" includes a vision of the distant human future, in outer space, followed by a vision of a lifeless earth and a final impending battle of the good and evil spiritual powers.

Entries were expected to be in heroic couplets, but Tennyson's entry was in Miltonic blank verse. Nevertheless, he won.

Tennyson didn't think his poem was any good, and called it "a wild and unmethodized performance". He was too embarrassed to read it himself at commencement, so the previous year's winner did it for him. For the rest of his life, he forbade publication of "Timbuctoo."

Tennyson did not sing the praises of England's world conquest. But he did not express any objections it, either. And Tennyson's later poetry showcases the "modern" expectation that the human race, guided by reason and science, would come together and build a better world for everyone. If you are a postmodernist, you won't like Tennyson.

Instead, "Timbuctoo" is about

how fantasy helps

the human race make progress. Whether or not we share

Tennyson's optimism about the ultimate triumph of human wisdom,

goodness, and science,

we have all built castles in the air. Tennyson would write

much better verse as an adult. But the theme of "Timbuctoo"

is still remarkable.

I stood upon the Mountain which o'erlooks

-- Chapman

The narrow seas, whose rapid interval

Parts Africa from green Europe, when the Sun

Had fall'n below th' Atlantick, and above

The silent Heavens were blench'd with faery light,

Uncertain whether faery light or cloud,

Flowing Southward, and the chasms of deep, deep blue

Slumber'd unfathomable, and the stars

Were flooded over with clear glory and pale.

Lines 1-9:

I gaz'd upon the sheeny coast beyond,

There where the Giant of old Time infixed

The limits of his prowess, pillars high

Long time eras'd from Earth: even as the Sea

When weary of wild inroad buildeth up

Hugh mounds whereby to stay his yeasty waves.

Lines 10-27:

As when in some great City where the walls

Shake, and the streets with ghastly faces throng'd

Do utter forth a subterranean voice,

Among the inner columns far retir'd

At midnight, in the lone Acropolis,

Before the awful Genius of the place

Kneels the pale Priestess in deep faith, the while

Above her head the weak lamp dips and winks

Unto the fearful summoning without:

Nathless she ever clasps the marble knees,

Bathes the cold hand with tears, and gazeth on

Those eyes which wear no light but that wherewith

Her phantasy informs them.

Lines 28-39:

Where are your moonlight halls, your cedarn glooms,

The blossoming abysses of your hills?

Your flowering Capes, and your gold-sanded bays

Blown round with happy airs of odorous winds?

Where are the infinite ways, which, Seraph-trod,

Wound thro' your great Elysian solitudes,

Whose lowest deeps were, as with visible love,

Fill'd with Divine effulgence, circumfus'd,

Flowing between the clear and polish'd stems,

And ever circling round their emerald cones

In coronals and glories, such as gird

The unfading foreheads of the Saints in Heaven?

For nothing visible, they say, had birth

In that blest ground but it was play'd about

With its peculiar glory.

Lines 40-56:

Of a young Seraph! And he stood beside me

There on the ridge, and look'd into my face

With his unutterable, shining orbs.

Lines 62-66:

So that with hasty motion I did veil

My vision with both hands, and saw before me

Such colour'd spots as dance athwart the eyes

Of those, that gaze upon the noonday Sun.

Lines 67-70:

Girt with a Zone of flashing gold beneath

His breast, and compass'd round about his brow

With triple arch of everchanging bows,

And circled with the glory of living light

And alternation of all hues, he stood.

Lines 71-75:

Which fill'd the Earth with passing loveliness,

And odours rapt from remote Paradise?

Thy sense is clogg'd with dull mortality,

Thy spirit fetter'd with the bond of clay:

Open thine eyes and see.'

Lines 76-83:

With its exceeding brightness, and the light

Of the great Angel Mind which look'd from out

The starry glowing of his restless eyes.

Lines 83-87:

I felt my soul grow mighty, and my Spirit

With supernatural excitation bound

Within me, and my mental eye grew large

With such a vast circumference of thought,

That in my vanity I seem'd to stand

Upon the outward verge and bound alone

Of full beatitude.

Lines 88-94:

Grew thrillingly distinct and keen. I saw

The smallest grain that dappled the dark Earth,

The indistinctest atom in deep air,

The Moon's white cities, and the opal width

Of her small glowing lakes, her silver heights

Unvisited with dew of vagrant cloud,

And the unsounded, undescended depth

Of her black hollows.

Lines 94-103:

Distinct and vivid with sharp points of light,

Blaze within blaze, an unimagin'd depth

And harmony of planet-girded Suns

And moon-encircled planets, wheel in wheel,

Arch'd the wan Sapphire.

And notes of busy life in distant worlds

Beat like a far wave on my anxious ear.

Lines 103-112:

Rapid as fire, inextricably link'd,

Expanding momently with every sight

And sound which struck the palpitating sense,

The issue of strong impulse, hurried through

The riv'n rapt brain;

Lines 113-119:

Disjointed, crumbling from their parent slope

At slender interval, the level calm

Is ridg'd with restless and increasing spheres

Which break upon each other, each th' effect

Of separate impulse, but more fleet and strong

Then its precursor, till the eye in vain

Amid the wild unrest of swimming shade

Dappled with hollow and alternate rise

Of interpenetrated arc, would scan

Definite round.

Lines 119-129:

From visible objects, for but dimly now,

Less vivid than an half-forgotten dream,

The memory of that mental excellence

Comes o'er me, and it may be I entwine

The indecision of my present mind

With its past clearness, yet it seems to me

As even then the torrent of quick thought

Absorbed me from the nature of itself

With its own fleetness.

Lines 130-140:

Could link his shallop to the fleeting edge,

And muse midway with philosophic calm

Upon the wondrous laws, which regulate

The fierceness of the bounding Element?

Lines 140-145:

Of rampart upon rampart, dome on dome,

Illimitable range of battlement

On battlement, and the Imperial height

Of Canopy o'ercanopied.

Lines 158-163:

Of Pyramids as far surpassing Earth's

As Heaven than Earth is fairer.

Lines 163-166:

Of wheeling Suns, or Stars, or semblances

Of either, showering circular abyss

Of radiance.

Lines 166-170:

Interminably high, if gold it were

Or metal more etherial, and beneath

Two doors of blinding brilliance, where no gaze

Might rest, stood open, and the eye could scan,

Through length of porch and valve and boundless hall,

Part of a throne of fiery flame, wherefrom

The snowy skirting of a garment hung,

And glimpse of multitudes of multitudes

That minister'd around it - if I saw

These things distinctly, for my human brain

Stagger'd beneath the vision, and thick night

Came down upon my eyelids, and I fell.

Lines 170-183:

Which but to look on for a moment fill'd

My eyes with irresistible sweet tears,

In accents of majestic melody,

Like a swoln river's gushings in still night

Mingled with floating music, thus he spake:

By shadowing forth the Unattainable;

And step by step to scale that mighty stair

Whose landing-place is wrapt about with clouds

Of glory' of Heaven.

Lines 191-196:

And in red Autumn when the winds are wild

With gambols, and when full-voiced Winter roofs

The headland with inviolate white snow,

I play about his heart a thousand ways,

Visit his eyes with visions, and his ears

With harmonies of wind and wave and wood,

-- Of winds which tell of waters, and of waters

Betraying the close kisses of the wind --

And win him unto me: and few there be

So gross of heart who have not felt and known

A higher than they see: They with dim eyes

Behold me darkling.

Lines 196-209:

My fullness; I have fill'd thy lips with power.

Lines 209-211:

I have rais'd thee nigher to the spheres of Heaven

Man's first, last home: and thou with ravish'd sense

Listenest the lordly music flowing from

Th' illimitable years.

Lines 212-215:

All th' intricate and labyrinthine veins

Of the great vine of Fable, which, outspread

With growth of shadowing leaf and clusters rare,

Reacheth to every corner under Heaven,

Deep-rooted in the living soil of truth;

So that men's hopes and fears take refuge in

The fragrance of its complicated glooms,

And cool impleached twilights.

Lines 215-224:

forth issuing from the darkness, windeth through

The argent streets o' th' City, imaging

The soft inversion of her tremulous Domes,

Her gardens frequent with the stately Palm,

Her Pagods hung with music of sweet bells,

Her obelisks of ranged Chrysolite,

Minarets and towers? Lo! How he passeth by,

And gulphs himself in sands, as not enduring

To carry through the world those waves, which bore

The reflex of my City in their depths.

Lines 224-235:

O City! O latest Throne! Where I was rais'd

To be a mystery of loveliness

Unto all eyes, the time is well-nigh come

When I must render up this glorious home

To keen Discovery: soon yon brilliant towers

Shall darken with the waving of her wand;

Darken, and shrink and shiver into huts,

Black specks amid a waste of dreary sand,

Low-built, mud-wall'd, Barbarian settlements.

How chang'd from this fair City!'

Was left alone on Calpe, and the Moon

Had fallen from the night, and all was dark!

Lines 245-248:

|

Fred imagined himself standing on the Rock of Gibraltar, looking from Europe to Africa. The sun had just set, the sky was dark, and Fred thought about how nobody knows how deep ocean canyons go.

| Lines 1-9 |

|

Fred looked for some of the old monuments that are described in Greek mythology. They weren't there.

Atlas was the giant who supposedly stood on the African side and held up the heavens. You can visit the Atlas Mountains on the African side. And the rocks on either side of the Straits of Gibraltar were supposedly the "pillars of Hercules", set up by the hero during his travels.

| Lines 10-27: |

|

Fred thought about mythology. Myths inspire people, even though people make them up. And people keep pursuing imaginary places.

The theme of people going to look for imaginary places for nobody-knows-why reappears in Tennyson's poem, "Ulysses". According to Dante, which is the source for Tennyson's poem, Ulysses's last voyage accomplished nothing except killing him and his crew. (At least Laing accomplished something.) In "The Charge of the Light Brigade", Tennyson honors the hundreds of soldiers who were sent to their deaths by their commander's stupidity. "Whilome" means "once upon a time."

| Lines 16-27: |

|

Fred compared mythology to somebody clinging to the image of a make-believe god during an earthquake, in spite of the rest of the town calling her to get out of the building.

Other people who have written about "Timbuctoo" have focused on this section, and seen this as testimony of his willingness to believe in traditional religion even as it collapsed in light of the scientific discoveries of his era. Perhaps Tennyson is clinging to the memory of a mystical experience that convinced him that deep faith is not a delusion. Perhaps he is wondering whether he is deceiving himself. During an earthquake, you don't want to be inside a large place of worship. (Do you know the story of the Lisbon earthquake?) The priestess can end up dead. "Nathless" means "nevertheless".

| Lines 28-39: |

|

Fred wondered whether there really are, or could be, any fantastic places in our world. If they exist, how is it possible?

| Lines 40-56: |

|

Looking over at Africa, Fred wondered about the legendary city of Timbuctoo, supposedly a high civilization in the interior of Africa.

| Lines 56-61: |

|

As Fred was thinking about all of this, an angel of bright light came down from heaven and faced him.

| Lines 62,66: |

|

Dazzled, Fred closed his eyes. He saw afterimages of the bright light.

| Lines 67-70: |

|

The angel was surrounded by shifting rainbows.

| Lines 71-75: |

|

The angel said, "Why keep thinking about the mythologies of the past? Look around you."

| Lines 76-83: |

|

Fred's eyes were suddenly opened.

| Lines 83-87: |

|

Supernatural power flowed into Fred. Suddenly he could see everything at once.

| Lines 88-94: |

|

All of Fred's other senses became hyperacute as well. He saw cities on the moon, with cloudless peaks and incredibly deep canyons.

| Lines 94-103: |

|

Then Fred could see our entire galaxy, with all its stars and planets around them. And then Fred heard human beings and other life-forms. They were living, talking, and carrying out their business on far-away planets all across the Milky Way. The galaxy no longer looked fuzzy, but each star was sharp and distinct. It still mades an arch across the night sky ("arch'd the wan sapphire.") Again, this came from "Armageddon". Tennyson described seeing space travel as if it were an actual vision of the human future. At the time, he was not pondering the influence of myths and poetic fantasy on human progress. If Tennyson actually heard the human race's future in space, it was not while he was thinking about the themes he chose for "Timbuctoo".

| Lines 103-112: |

|

Fred's thoughts came incredibly fast. He seemed to know all manner of things and to understand their interconnectedness.

| Lines 113-119: |

|

This is a roundabout way of describing ripples in a pond, making an epic simile. Tennyson's experience was like groups of ripple patterns in a lake, coming together and producing interference patterns.

You've seen interference patterns when two layers of nylon stocking are moved across each other. The gridwork in each produces the semblance of complex lines. Interference / maoire patterns seem real too, but aren't.

| Lines 119-129: |

|

There was no way that Fred could put this experience into words, or describe it accurately, and he cannot remember most of it anyway. It was like being caught up in the onrush of a river.

| Lines 130-140: |

|

Caught up, Fred felt like he was shooting the rapids in a canoe. There was no time to think.

| Lines 140-145: |

|

Fred's experience changed his entire way of thinking.

| Lines 146-157: |

|

And then Fred saw the magical land of Timbuctoo.

"Pile" is a fabric of interconnected threads, like the "pile" of a rug.

| Lines 158-163: |

|

The Timbuctoo that Fred saw was a fantastic, glowing city.

| Lines 163-166: |

|

Timbuctoo was a little universe, with its own stars and planets.

| Lines 166-170: |

|

Finally Fred saw a central sanctuary, which recalled a famous Old Testament vision of God on His throne.

| Lines 170-183: |

|

Happy and sad at the same time, the angel identified himself as the spirit of Fable, or Fantasy. His job is to sway the human heart, by make-believe, so that the human race will make progress. The future in outer space may have been the real human future. Timbuctoo is today's make-believe, which inspires people to look for better worlds.

| Lines 191-196: |

|

Fantasy makes people imagine and believe in things they cannot see. Even ordinary folks sense the transcendent, and express it in mythology.

| Lines 196-209: |

|

The angel commissioned Fred as a poet for the human race.

| Lines 209-211: |

|

The angel told Fred that people would always be guided by the visions of poets.

| Lines 212-215: |

|

Fantasy and fable are based on reality, and they give people a way to make sense of their hopes and fears.

| Lines 215-224: |

|

The Timbuctoo River reflected the city. And it carries that reflection out toward the rest of the world. But now... the river has begun to dissipate in the Sahara desert.

| Lines 224-235: |

|

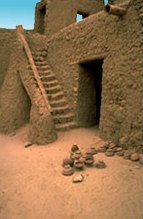

For better or worse, the actual, real-world Timbuctoo is about to be discovered by Europeans. The city is nothing more than a bunch of mud buildings in the middle of the Sahara desert.

When Tennyson wrote about the passing of King Arthur, he told how Sir Bedivere kept refusing to throw the magic sword back into the lake. When he finally does so, he sees the promise of a better future. We must abandon the things of the pre-scientific age, but there is a promise of something better still to come. Space travel awaits us.

| Lines 236-245: |

|

Fred was left alone in the dark with his thoughts.

The suggestion is that Tennyson, now commissioned as a poet, needs to find answers for his society, after they can no longer believe in the magical land of "Timbuctoo". For the rest of his life, he would wonder about how the here-and-now world described by science relates to art, religion, and mysticism. "Calpe" is just an archaic name for Gibraltar.

| Lines 245-248: |

Poetic license?

Tennyson might have read accounts of mystics to create, or at least embellish, his own supposed experience.

No!

Cosmic consciousness?

The best introduction to this type of experience is the classic study by William James. If you are a student, this would be a good link to follow now.

As a kid, Tennyson discovered he could bring on a "kind of waking trance" by repeating a single word over and over. After a while, he would experience an expansion of his mind, with a hightened sense of who he was followed by a sudden change in which only the infinite seemed real. Mystics agree that these experiences can't be put into words.

Tennyson seems to be writing about this in "Armageddon", the poem which he wrote at age 15 and which he cannibalized for "Timbuctoo".

I wondered with deep wonder at myself,

My mind seem'd wing'd with knowledge and the strength

Of holy musings and immense Ideas

Even to Infinitude. All sense of Time

And Being and Place was swallowed up and lost

I was part of the Unchangeable,

A scintillation of Eternal Mind,

Remix'd and burning with its parent fire.

No!

If this had happened to Tennyson, it is surprising that he later became the great poet of the ongoing struggles of faith and doubt.

Ordinary dream?

Creative artists have drawn on their vivid dreams from time to time.

No!

I don't think anybody could take his ordinary dreams this seriously.

On drugs?

Thomas DeQuincy wrote at length about his opium hallucinations. Coleridge claimed (maybe falsely) that his "Kubla Khan" vision of a fantastic city came to him in an opium dream. We can't be sure what was in their opium, and this stuff was widely available in his society.

And who knows what might have been available to Fred, in school with some of the more enterprising teens of his era? Mescaline and psilocybin are only two possibilities.

No!

Opium visions as reported by DeQuincy were fragmented and meaningless.

Mental illness?

In addition to his father, Tennyson had several other close relatives who suffered from major mental illness. Tennyson had already begun to suffer from episodes of despondency.

Elsewhere, I have argued that William Blake was schizophrenic, and kept the process under control through his work as an engraver, and by his artistic genius. This has gotten me a lot of personal attacks, but no counter-arguments beyond that fact that we have insufficient information to fit researcher's criteria. Mr. Blake wrote an account, in a personal letter, of a seeing-everything experience similar to Tennyson's.

No!

This is in sharp contrast to Blake, whose contemporaries talked about how his genius and his madness went together.

Something else?

Tennyson's experience does not fit neatly into any of the above categories.

No!

I'd like to hear your ideas.

My best answer:

Tennyson's best

buddy (Arthur Hallam)

died suddenly of a berry aneurysm. Tennyson's poem, "In Memoriam",

deals with the perpetual human search for an answer for death.

His lines: have probably prevented at least a few suicides following

failed relationships.

"Locksley Hall" includes a vision of war in the air and

planes dropping bombs on cities. (Did Tennyson see

the future once again?)

It was followed (as we can hope it will be in

our era) by the good people of the world

uniting and finding how to live in peace.

Tennyson became poet laureate,

and was made a baron for his literary work as spokesperson

for his era. You'll hear him called Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Tennyson

More on Tennyson

'Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.

Tennyson --

send a poem to a friend

The Lady of Shalott -- also by Ed

Tennyson --

Brown U.

Piers Plowman. Fictional dream-vision by a proto-Protestant.

Among other subjects, there is an allegory ("Maid Meed") of how

Christians are to respond to the rise of free enterprise

and the profit motive.

Lamia

Part I and Part II,

by Keats. A rational philosopher ruins the lovers' happiness

by pointing out it's all a lie.

The

Triumph of Life, an unfinished manuscript poem by Percy Shelley, is a good read.

"The world won't accept my progressive social ideas. So is

life with living? Is my answer to withdraw into mysticism?"

Renascence

by Edna St. Vincent Millay. More cosmic consciousness?

Timbuktu is in what is now Mali. The name means "mother with the big navel." Once it was a trading center and the home of a Muslim institute. There were salt mines to the north, and gold mines to the south. All that remains is a small desert community.

Leo

Africanus description of the medieval city

Jewish Roots in Timbuktu

LonelyPlanet

Mr. Dowling

High

on Adventure

Saga Tours, customized

for visitors to Timbuktu

Early

European explorations

Timbuktu Books, no longer online, was a group of

African-American specialty booksellers.

Again, Timbuktu is an ideal for good living.

To think about:

Don't write me asking for answers. I don't know.

| New visitors to www.pathguy.com reset Jan. 30, 2005: |

If you'll e-mail me a good short poem on the subject of Timbuktu, I'll place it here!

The last is a naughty joke. If you've gotten this far, you're old enough. But please stop reading here if this will be a problem for you.

In 1970, as an English major at Brown, I was introduced to Tennyson's life and work. I made up this joke. Others must have done the same independently. I have heard it from time to time, though never with reference to Tennyson.

Every year, the Ivy League holds a contest to see who has the best poet. Last year, the two final contestants were the poet from Brown and the poet from _____.The master of ceremonies opened his envelope and announced, "For the final round of the Ivy League Poetry Contest, each of you must recite an extemporaneous poem on the subject of Timbuctoo."

The poet from Brown thought for a moment, and said...

As I was walking by the sea,

A little ship sailed up to me,

A silver ship, with sails all white

That sparkled in the morning light.

A gentle breeze was on the air,

I climbed aboard that ship so fair

And sailed away the ocean blue

To the far shores of Timbuctoo.The poet from _____ thought for a moment, and said...

Me and Tim was hunting deer.

Three lady hunters done appear.

Me and Tim knowed what to do.

Me buck one and Tim buck two.

Try one of Ed's chess-with-a-difference java applets!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|