by Ed Friedlander, M.D.

scalpel_blade@yahoo.com

No texting or chat messages, please. Ordinary e-mails are welcome.

This pursued through volumes might take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

-- Keats (Dec. 21, 1817)

I'm a physician and medical school teacher in real life. I've liked Keats since I was in high school. Generally I enjoy the classics because they say what most of us have thought, but much more clearly.

The real John Keats is far more interesting than the languid aesthete of popular myth. Keats was born in 1795, the son of a stable attendant. As a young teen, he was extroverted, scrappy, and liked fistfighting. In 1810 he became an apprentice to an apothecary-surgeon, and in 1815 he went to medical school at Guy's Hospital in London. In 1816, although he could have been licensed to prepare and sell medicines, he chose to devote his life entirely to writing poetry.

In 1818, Keats took a walking tour of the north of England and Scotland, and nursed his brother Tom during his fatal episode of tuberculosis.

By 1819, Keats realized that he, too, had tuberculosis. If you believe that most adult TB is from reactivation of a childhood infection, then he probably caught it from his mother. If you believe (as I do) that primary progressive TB is common, then he may well have caught it from Tom. Or it could have come from anybody. TB was common in Keats's era.

Despite his illness and his financial difficulties, Keats wrote a tremendous amount of great poetry during 1819, including "La Belle Dame Sans Merci".

On Feb. 3, 1820, Keats went to bed feverish and feeling very ill. He coughed, and noticed blood on the sheet. His friend Charles Brown looked at the blood with him. Keats said, "I know the color of that blood; it is arterial blood. I cannot be deceived. That drop of blood is my death warrant." (Actually, TB is more likely to invade veins than arteries, but the blood that gets coughed up turns equally red the instant it contacts oxygen in the airways. The physicians of Keats's era confused brown, altered blood with "venous blood", and fresh red blood with "arterial blood".) Later that night he had massive hemoptysis.

Seeking a climate that might help him recover, he left England for Italy in 1820, where he died of his tuberculosis on Feb. 23, 1821. His asked that his epitaph read, "Here lies one whose name was writ in water."

Percy Shelley, in "Adonais", for his own political reasons, claimed falsely that bad reviews of Keats's poems (Blackwoods, 1817) had caused Keats's death. Charles Brown referred to Keats's "enemies" on Keats's tombstone to get back at those who had cared for him during his final illness. And so began the nonsense about Keats, the great poet of sensuality and beauty, being a sissy and a crybaby.

There is actually much of the modern rock-and-roll star in Keats. His lyrics make sense, he tried hard to preserve his health, and he found beauty in the simplest things rather than in drugs (which were available in his era) or wild behavior. But in giving in totally to the experiences and sensations of the moment, without reasoning everything out, Keats could have been any of a host of present-day radical rockers.

O for a Life of Sensations rather than of Thoughts! It is a "Vision in the form of Youth" a shadow of reality to come and this consideration has further convinced me... that we shall enjoy ourselves here after having what we called happiness on Earth repeated in a finer tone and so repeated. And yet such a fate can only befall those who delight in Sensation rather than hunger as you do after Truth.

-- Keats to Benjamin Bailey, Nov. 22, 1817

If you are curious to learn more about Keats, you'll find he was tough, resilient, and likeable.

"La Belle Dame Sans Merci" exists in two versions. The first was the original one penned by Keats on April 21, 1819. The second was altered (probably at the suggestion of Leigh Hunt, and you might decide mostly for the worse) for its publication in Hunt's Indicator on May 20, 1819.

|

Manuscript I

Oh what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Oh what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

I see a lily on thy brow,

I met a lady in the meads,

I made a garland for her head,

I set her on my pacing steed,

She found me roots of relish sweet,

She took me to her elfin grot,

And there she lulled me asleep

I saw pale kings and princes too,

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

And this is why I sojourn here

|

Published I

Ah, what can ail thee, wretched wight, II

Ah, what can ail thee, wretched wight, III

I see a lily on thy brow, IV

I met a lady in the meads, V

I set her on my pacing steed, VI

I made a garland for her head, VII

She found me roots of relish sweet, VIII

She took me to her elfin grot, IX

And there we slumber'd on the moss, X

I saw pale kings, and princes too, XI

I saw their starved lips in the gloam, XII

And this is why I sojourn here,

|

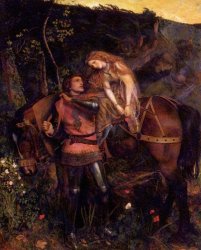

The poet meets a knight by a woodland lake in late autumn. The man has been there for a long time, and is evidently dying.

The knight says he met a beautiful, wild-looking woman in a meadow. He visited with her, and decked her with flowers. She did not speak, but looked and sighed as if she loved him. He gave her his horse to ride, and he walked beside them. He saw nothing but her, because she leaned over in his face and sang a mysterious song. She spoke a language he could not understand, but he was confident she said she loved him. He kissed her to sleep, and fell asleep himself.

He dreamed of a host of kings, princes, and warriors, all pale as death. They shouted a terrible warning -- they were the woman's slaves. And now he was her slave, too.

Awakening, the woman was gone, and the knight was left on the cold hillside.

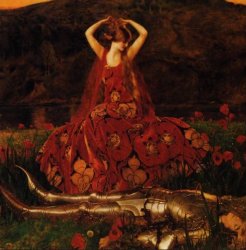

"La Belle Dame Sans Merci" means "the beautiful woman without mercy." It's the title of an old French court poem by Alain Chartier. ("Merci" in today's French is of course "thank you".) Keats probably knew a current translation which was supposed to be by Chaucer. In Keats's "Eve of Saint Agnes", the lover sings this old song as he is awakening his beloved.

"Wight" is an archaic name for a person. Like most people, I prefer "knight at arms" to "wretched wight", and obviously the illustrators of the poem did, too. ("Until I met her, I was a man of action!")

"Sedge" is any of several grassy marsh plants which can dominate a wet meadow.

"Fever dew" is the sweat (diaphoresis) of sickness. Keats originally wrote "death's lily" and "death's rose", and he refers to the flush and the pallor of illness. If the poet can actually see the normal red color leaving the cheeks of the knight, then the knight must be going rapidly into shock, i.e., the poet has come across the knight right as he is dying, and is recording his last words. (The knight is too enwrapped in his own experience to notice.)

Medieval fairies (dwellers in the realm of faerie) were usually human-sized, though Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream allowed them (by negative capability) to be sometimes-diminutive.

"Sidelong" means sideways. A "fragrant zone" is a flower belt. "Elfin" means "pertaining to the elves", or the fairy world. A "grot" is of course a grotto. "Betide" means "happen", and "woe betide" is a more romantical version of the contemporary expression "---- happens". "Gloam" means gloom. A "thrall" is an abject slave.

Keats had a voluminous correspondence, and we can reconstruct the events surrounding the writing of "La Belle Dame Sans Merci". He wrote the poem on April 21, 1819. It appears in the course of a letter to his brother George, usually numbered 123. You may enjoy looking this up to see how he changed the poem even while he was writing it.

At the time, Keats was very upset over a hoax that had been played on his brother Tom, who was deceived in a romantic liaison. He was also undecided about whether to enter into a relationship with Fanny Brawne, who he loved but whose friends disapproved of the possible match with Keats.

Shortly before the poem was written, Keats recorded a dream in which he met a beautiful woman in a magic place which turned out to be filled with pallid, enslaved lovers.

Just before the poem was written, Keats had read Spenser's account of the false Florimel, in which an enchantress impersonates a heroine to her boyfriend, and then vanishes.

All these experiences probably went into the making of this powerful lyric.

In the letter, Keats followed the poem with a chuckle.

Why four kisses -- you will way -- why four? Because I wish to restrain the headlong impetuosity of my Muse -- she would have fain said "score" without hurting the rhyme -- but we must temper the imagination as the critics say with judgment. I was obliged to choose an even number that both eyes might have fair play: and to speak truly I think two apiece quite sufficient. Suppose I had said seven; there would have been three and a half apiece -- a very awkward affair -- and well got out of on my side --

John Keats's major works do not focus on religion, ethics, morals, or politics. He mostly just writes about sensations and experiencing the richness of life.

In his On Melancholy, Keats suggests that if you want to write sad poetry, don't try to dull your senses, but focus on intense experience (not even always pleasant -- peonies are nice, being b_tched out by your girlfriend isn't), and remember that all things are transient. Only a poet can really savor the sadness of that insight.

In Lamia, a magic female snake falls in love with a young man, and transforms by magic into a woman. They live together in joy, until a well-intentioned scholar ruins the lovers' happiness by pointing out that it's a deception. Until the magic spell is broken by the voice of reason and science, they are both sublimely happy. It invites comparison with "La Belle Dame Sans Merci".

- Richard Dawkins took a line from "Lamia" for the title of his book,

Unweaving the Rainbow, against

the familiar (romantic?) complaints

that studying nature (as it really is) makes you less appreciative of

the world's beauty. (I agree with Dawkins.

I haven't found that being scientific spoils anybody's appreciation

of beauty. -- Ed.)

To a Nightingale recounts Keats's being enraptured (by a singing bird) out of his everyday reality. He stopped thinking and reasoning for a while, and after the experience was over, he wondered which state of consciousness was the real one and which was the dream.

To Autumn is richly sensual, and contrasts the joys of autumn to the more-poetized joys of spring. Keats was dying at the time, and as in "La Belle Dame Sans Merci", Keats is probably describing, on one level, his own final illness -- a time of completion, consummation, and peace.

Ask your instructor about Keats's "pleasure thermometer". The pleasure of nature and music gives way to the pleasure of sexuality and romance which in turn give way to the pleasure of visionary dreaming.

Keats focuses on how experiencing beauty gives meaning and value to life. In "La Belle Dame Sans Merci", Keats seems to be telling us about something that may have happened, or may happen someday, to you.

You discover something that you think you really like. You don't really understand it, but you're sure it's the best thing that's ever happened to you. You are thrilled. You focus on it. You give in to the beauty and richness and pleasure, and let it overwhelm you.

Then the pleasure is gone. Far more than a normal letdown, the experience has left you crippled emotionally. At least for a while, you don't talk about regretting the experience. And it remains an important part of who you feel that you are.

Drug addiction (cocaine, heroin, alcohol) is what comes

to my mind first. We've all known addicts who've tasted the

pleasures, then suffered the health, emotional, and personal consequences.

Yet I've been struck by how hard it is to rehabilitate these

people, even when hope seems to be gone. They prefer to stagnate.

Drug addiction (cocaine, heroin, alcohol) is what comes

to my mind first. We've all known addicts who've tasted the

pleasures, then suffered the health, emotional, and personal consequences.

Yet I've been struck by how hard it is to rehabilitate these

people, even when hope seems to be gone. They prefer to stagnate.

Vampires were starting to appear in literature around Keats's time, and the enchantress of "La Belle Dame Sans Merci" is one of a long tradition of supernatural beings who have charmed mortals into spiritual slavery. Bram Stoker's "Dracula" got much of its bite from the sexuality and seductiveness of the vampire lord.

Anyone who has seen or read "Coraline" can explore whether the "Beldame", who offers love and then imprisons her victims, is related to Keats's "Belle Dame". Explore the origins of the word in folklore. The theme of "Coraline" seems to be that if parents do not give attention to, and attend to the emotional needs of, their children... then other people will. And they will be the wrong people.

Failed romantic relationships (ended romances, marriages with the love gone) account for an astonishing number of suicides. Rather than giving up and moving on, men and women find themselves disabled, but not expressing sorrow that the relationship occurred.

Ideologies bring enormous excitement and happiness to new believers. They offer camaraderie and the thrill of thinking that you are intellectually and morally superior and about to change the world for the better. Members of both the Goofy Right and the Goofy Left seemed very happy on my college campus, and I've seen the satisfaction that participation in ideological movements brings people ever since. People who leave these movements (finding out that the movements are founded on lies) are often profoundly saddened and lonely.

Religious emotionalism can have an enormous impact, and some lives are permanently changed for the better at revivals. But some people who have come upon a faith commitment emotionally find themselves devastated when the emotions fade, and become unable to function even at their old level.

The Vilia is a Celtic woodland spirit, celebrated by Lehar and Ross in a love song from "The Merry Widow", 1905. The song itself was popular during the 1950's. The song deals with a common human experience -- never being able to recover the first ardor of love. The show itself celebrates that people CAN find love again.

The wood maiden smiled and no answer she gave,

Vilia -- organ chorded version

There once was a VIlia, a witch of the wood,

A hunter beheld her alone as she stood,

The spell of her beauty upon him was laid;

He looked and he longed for the magical maid!

For a sudden tremor ran,

Right through the love bwildered man,

And he sighed as a hapless lover can.

Vilia, O Vilia! the witch of the wood!

Would I not die for you, dear, if I could?

Vilia, O Vilia, my love and my bride,

Softly and sadly he sighed.

But beckoned him into the shade of the cave,

He never had known such a rapturous bliss,

No maiden of mortals so sweetly can kiss!

As before her feet he lay,

She vanished in the wood away,

And he called vainly till his dying day!

Vilia, O Vilia, my love and my bride!

Softly and sadly he sighed,

Sadly he sighed, "Vilia."

Vilia -- Chet Atkins, jazzier guitar version

Beauty itself, fully appreciated (as only a poet can), must by its impermanence devastate a person. Or so wrote Keats in his "To Melancholy", where the souls of poets hang as "cloudy trophies" in the shrine of Melancholy.

- My experience has been more in keeping with Blake's:

"He who kisses a joy as it flies / Lives in eternity's sunrise."

In "La Belle Dame Sans Merci" Keats is letting the reader decide whether the knight's experience was worth it. Keats (the master of negative capability) records no reply to the dying knight.

- simple language;

- medieval subject matter;

- supernatural subject matter;

- emphasis on beauty, emotion, and sensuality;

- emphasis on unreason.

To include this page in a bibliography, you may use this format: Friedlander ER (1999) Enjoying "La Belle Dame Sans Merci" by John Keats Retrieved Dec. 25, 2003 from http://www.pathguy.com/lbdsm.htm

For Modern Language Association sticklers, the name of the site itself is "The Pathology Guy" and the Sponsoring Institution or Organization is Ed Friedlander MD.

Links

Keats

Keats Biography

Yahoo on John Keats

Keats

Keats

Negative

Capability

www.john-keats.com

Thomas

of Erceldoune (Thomas the Rhymer)

was another mortal who was taken by the fairies to their

realm where they live in prosperity, peace, and delight -- as Satan's cattle.

U. Florida drawings

of sedges, etc.

"English Teaching Life"

has evidently used this page to instruct people who are learning the language.

I am very pleased by this, and commend Jan as a teacher.

There's something else.

As I've mentioned, Keats does not deal with conventional religion in his poems. In several of his private letters, he explicitly stated that he did not believe in Christianity, or in any of the other received faiths of his era.

As he faced death, it's clear that Keats did struggle to find meaning in life. And in the same letter (123) that contains the original of "La Belle Dame Sans Merci", Keats gives his answer.

The common cognomen of this world among the misguided and superstitious is "a vale of tears" from which we are to be redeemed by a certain arbitrary interposition of God and taken to Heaven. What a little circumscribed straightened notion!Call the world, if you please, "the Vale of Soul Making". Then you will find out the use of the world....

There may be intelligences or sparks of the divinity in millions -- but they are not Souls till they acquire identities, till each one is personally itself.

Intelligences are atoms of perception -- they know and they see and they are pure, in short they are God. How then are Souls to be made? How then are these sparks which are God to have identity given them -- so as ever to possess a bliss peculiar to each one's individual existence. How, but in the medium of a world like this?

This point I sincerely wish to consider, because I think it a grander system of salvation than the Christian religion -- or rather it is a system of Spirit Creation...

I can scarcely express what I but dimly perceive -- and yet I think I perceive it -- that you may judge the more clearly I will put it in the most homely form possible. I will call the world a school instituted for the purpose of teaching little children to read. I will call the human heart the hornbook used in that school. And I will call the child able to read, the soul made from that school and its hornbook.

Do you not see how necessary a world of pains and troubles is to school an intelligence and make it a soul? A place where the heart must feel and suffer in a thousand diverse ways....

As various as the lives of men are -- so various become their souls, and thus does God make individual beings, souls, identical souls of the sparks of his own essence.

This appears to me a faint sketch of a system of salvation which does not affront our reason and humanity...

Keats believed that we begin as identical bits of God, and acquire individuality only by life-defining emotional experiences. By doing this, we prepare ourselves for happiness in the afterlife.

You may decide for yourself (or exercise negative capability) about whether you will believe Keats. But it's significant that this most intimate explanation of the personal philosophy behind his work follows a powerful lyric about emotional devastation.

If Keats's philosophy is correct, then any intense experience -- even letting your life rot away after a failed relationship, or enduring the agony of heroin withdrawal, or dying young of tuberculosis -- is precious. (Perhaps Keats, medically trained and knowing he had been massively exposed, was foreseeing his own from TB -- he would have been pale and sweaty and unable to move easily.) Each goes into making you into a unique being.

The idea is as radical as it sounds. And if you stay alert, you'll encounter similar ideas again and again, in some of the most surprising places.

Diotima

He who from these ascending under the influence of true love, begins to perceive that beauty, is not far from the end. And the true order of going, or being led by another, to the things of love, is to begin from the beauties of earth and mount upwards for the sake of that other beauty, using these as steps only, and from one going on to two, and from two to all fair forms, and from fair forms to fair practices, and from fair practices to fair notions, until from fair notions he arrives at the notion of absolute beauty, and at last knows what the essence of beauty is.

Monty Python's "The Meaning of Life"

In the universe, there are many energy fields which we cannot normally perceive. Some energies have a spiritual source, which act upon a person's soul. The soul does not exist ab initio, as orthodox Christianity teaches. It has to be brought into existence by a process of guided self-observation. However, this is rarely achieved, owing to man's unique ability to be distracted from spiritual matters by everyday trivia.Planescape -- adventure gaming based on philosophies of life, where the Sensate faction lives out Keats's ideals.

Dean Koontz, "Intensity"

Mr. Vess is not sure if there is such a thing as the immortal soul, but he is unshakably certain that if souls exist, we are not born with them in the same way that we are born with eyes and ears. He believes that the soul, if real, accretes in the same manner as a coral reef grows from the deposit of countless millions of calcareous skeletons secreted by marine polyp. We build the reef of the soul, however, not from dead polyps but from steadily accreted sensations through the course of a lifetime. In Vess's considered opinion, if one wishes to have a formidable soul -- or any soul at all -- one must open oneself to every possible sensation, plunge into the bottomless ocean of sensory stimuli that is our world, and experience with no consideration of good or bad, right or wrong, with no fear but only fortitude.

I'm an MD, a

pathologist in Kansas City,

a mainstream Christian.

a modernist, a

skydiver, an adventure gamer,

the world's busiest free

internet physician,

and a man who still

enjoys books and ideas.

I'm an MD, a

pathologist in Kansas City,

a mainstream Christian.

a modernist, a

skydiver, an adventure gamer,

the world's busiest free

internet physician,

and a man who still

enjoys books and ideas.

Visit my home page

E-mail me

Brown University,

Department of English -- my home base, 1969-1973.

More of my stuff:

Antony & Cleopatra -- just getting started

The Book of Thel

Hamlet

Julian of Norwich

King Lear

The Lady of Shalott

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Macbeth

Moby Dick

Oedipus the King

Prometheus Bound

Romeo and Juliet -- just a short note

The Knight's Tale

The Seven Against Thebes

The Tyger

Timbuctoo

Twelfth Night

| New visitors to www.pathguy.com reset Jan. 30, 2005: |

I do not possess Keats's negative capability.

You get over a failed relationship by making a conscious decision to do so.

I want to grab the

horseman in the poem and yell, "Cowboy up!" or something. I suspect

most visitors to this page would want to

do exactly the same thing.

If I don't share

Keats's focus on beauty and sensation over everything else, I do

appreciate him for his insights into the human heart.

Teens:

Stay away from drugs, work yourself extremely hard in class or

at your trade, play sports if and only if you like it,

and get out of abusive relationships by any means.

If the grown-ups who support you are "difficult", act

like you love them even if you're not sure that you do.

It'll help you and them.

The best thing anybody can say about you is, "That kid likes to

work too hard and isn't taking it easy like other young people." Health and friendship.

Like Keats, I had tuberculosis in 1978-82. It was memorable. I'm grateful to modern, reality-based science for my cure.